Reflections on the state of the world, on a bus journey from Miami to Atlanta.

Miami bus station sits in the shadow of the city’s sprawling, palatial airport. The taxi driver who brought me here said he would never take a bus to where I’m going. When his daughter traveled down from north Florida for Spring Break, he bought her a plane ticket.

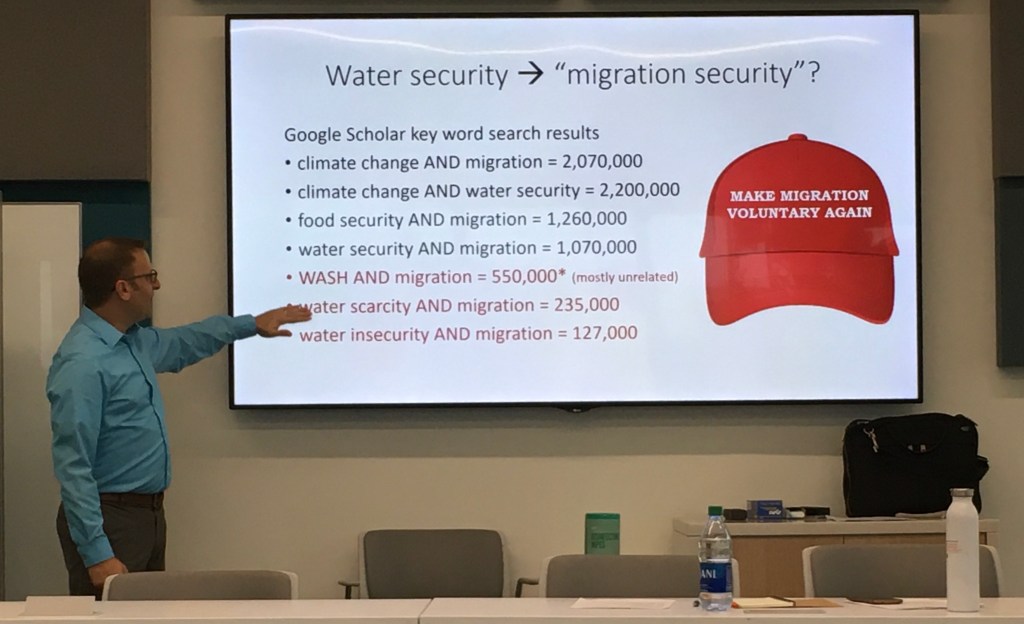

I don’t tell him my reasons for traveling by bus, but it’s because I’m trying to minimize my carbon footprint. I’d traveled to Florida from the UK for a workshop on climate change, water insecurity, and migration. The irony of my own contribution to the problems the workshop sought to address was not lost on me. While I couldn’t easily substitute low-carbon means of transport for the transatlantic flights, I was happy to find I could get to Atlanta (to see family) by bus.

The bus for Atlanta is due to leave at 7AM; the journey takes 14 hours. Nervous about missing the bus, I’d left my hotel without breakfast, and I’m disappointed to find that there’s no coffee shop in the station – only vending machines selling things I don’t want to eat. Caffeine-deprived and slightly dazed, I sit in the waiting room watching coverage of the coronavirus epidemic in Hong Kong, and ads for COPD drugs (two different kinds) and IUDs.

Once on the bus, I doze most of the way to Orlando, and then spring off in hope of finding food and coffee. Orlando’s bus station is more substantial than Miami’s, but the landscape around it is bleak. A mile or so down the 8-lane highway, I spy a pair of Golden Arches on the horizon. I’ve never in my life been so happy to see a McDonald’s!

Back on the bus with food in my stomach and a cup of coffee in my hand, I notice place-names attesting to the peoples who once lived on this land — Ocala, Apopko, Ocoee, Alachua. On the interstate I amuse myself reading billboards. There are signs for doctors and lawyers (INJURED? Call this number. / THE LEADER in minimally invasive heart surgery…). Biblical signs (There’s nothing too hard for GOD. / FORGIVE. Obey 10 Commandments). And signs celebrating local products – oranges, peaches, pecans, Vidalia onions….

+++

Late in the afternoon, we cross the Georgia state line. The land here is marshy; standing water beneath the slender trees reflects the sunlight. In Tifton, GA, the moon rises over a dilapidated gas station, and a woman drives her children home in a golf cart.

The journey reminds me of things I love about America – the beauty of its landscape, the diversity. It also reminds me of things I deplore – the inequalities, the threadbare social contract. Some of the people on the bus looked in good health, but many looked tired, worn down by life. At our rest stops, the built environment was hostile to pedestrians; walkable public spaces were few and far between.

Hovering over us was the spectre of coronavirus, I wrote in my report on the workshop in Miami. And the virus coloured my reading of the signs I saw along the road. In each sign, it seemed, it was the same smiling White man (in the guise of doctor, lawyer, or preacher) promoting injury claims, heart surgery, and salvation – at a price. Public goods (justice, health, morality) being marketed as commodities. The perversity of this system should be clear to a five-year-old; and yet many of us grown-ups are inured to it, apt to take this rotten set of arrangements for granted.

As Shirley Lindenbaum has observed, epidemics can serve as sampling devices, highlighting connections that are otherwise hard to see. Coronavirus, which poses greater risks to the lives of those who are already vulnerable (in terms of advanced age, compromised respiratory or immune systems, or difficulty accessing medical care), is likely to show up – like a disclosing tablet – inequalities that have too long been ignored.

That’s the good news.

The bad news is that the epidemic – like the climate crisis that is continuing in the background – will cause many more needless deaths, and a great deal of suffering.

+++

Outside Atlanta, the freeway is gridlocked. For an hour, we inch along, a chain of tail lights snaking through the darkness.

I remember how, as a child, I found it comforting to watch the lights curl by on car journeys with my father. Back then I didn’t appreciate the dangers of the road. How could it be dangerous? I had a sense (Do all children feel this?) that the way the society around me worked was the right way, the good way.

When did I abandon that? I can’t place it, but at some point I came to recognise that the news on TV was coming to me through some kind of filter. There were contradictions in the stories we told about ourselves and our country. Our leaders weren’t always to be trusted.

DRIVE ALERT

ARRIVE ALIVE

In downtown Atlanta, we pass the gleaming dome of the state capitol, and, dwarfing it, the huge edifice of Grady Hospital, one of the largest in the country.

How, I wonder, can a country with so many human and technical resources — with the finest scientists and the greatest concentrations of wealth in the world — how can it, of all nations, fail to rise to the challenges of our time?

— It can fail, a voice in my head tells me. It may well fail. Because science and wealth are not all that’s needed. Because climate change and pandemics are not simply technical problems, but problems of politics.